japan: koya-san, kyoto, kyushu

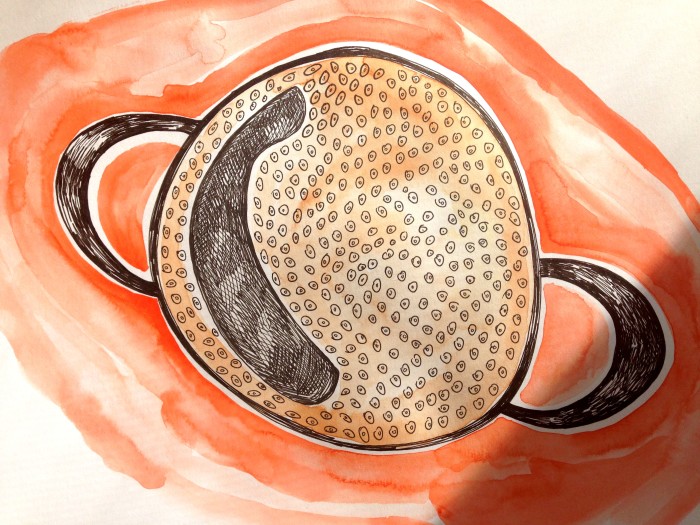

I’m worried I won’t find my mother at the airport in Tokyo. I see her walking her usual stride: tiny quick steps, sometimes when she is in a rush her torso moves faster than her legs. She sits down next to me with excitement. We’re both like schoolgirls, bubbling, we haven’t returned to Japan in ten years. We arrive in Osaka yawning from the long flight. The small plane from Narita was almost empty. Most of the passengers were asleep during the turbulent flight, but I stared down at Mt. Fuji, emerging from the clouds like a blue nipple. The flight attendant told us in her melodious voice that the turbulence would not affect the safety of the aircraft. We eat cucumber pickles and onigiri grilled in shoyu. The rice ball has a hot brown crust. I eat two in five minutes, drink water, and go to sleep. The next day we wake up at five, our stomachs so empty we can hear them echoing as we brush our teeth. We eat a gigantic breakfast of rice, miso soup, pickles, tiny white fish (baby anchovies), gyoza, sticky rice, soft-boiled egg, and seaweed. The streets of Osaka are quiet, clean and smooth, like the surface of a manicured nail. The only sound is the beep of the streetlight when it turns green. At lunchtime we sit at a counter and watch a man pour batter onto cabbage for okonomiyaki. He makes two for us: one with cabbage and pork, the other with green leeks and pork. One is draped with a shoyu lemon sauce. We stab at them with our chopsticks while they sizzle on the hot metal plate.

Koya-san is in the mountains. There are Buddhist temples at every curve of the road. We stay at two different temples, though our favorite is Eko-in. I like its simplicity, and though the food is better at the other temple according to my mother, I know I’ll be returning to Eko-in. There’s a sign above the faucet saying: Only water comes out. It should say, only cold water comes out. The instructions for morning meditation say, “if you have difficulty sitting on the floor during meditation we can provide you with a chair.” I laugh imagining myself sitting in a tall chair while my mother is on her knees with the monks. After meditating at six we are greeted with a shojin ryori feast, the Zen Buddhist cuisine. My mother’s friend tells us that it is difficult for women to travel alone in Japan because hotels are hesitant to rent a room to a single woman. Why? I ask. Because women have a history of hanging themselves with the belt of a yukata robe, she says. She mimes the gesture of strangling and points at the wooden beam above our heads. We continue eating our vegetarian breakfast. We are told that the monks grind sesame for hours to make gomadofu, sesame tofu.

I walk down the winding, wet road and come across colorful wind chimes flapping outside a small café. I’m transported to my Rudolf Steiner years in Australia. Bon on Shya Café is owned by a French-Japanese couple. She is French and he is Japanese, a musician, fluent in Italian, French, and English. Véronique is an artist and has drawn a beautiful children’s book. My mother wants to purchase it but they haven’t found a publisher yet. Véronique’s childhood reminds me of my own. She was born in the US and moved to France when she was nine and then traveled the world. She lived in Greenpoint as an adult, and arrived to Japan with her husband seven years ago. How did you choose Koya-san? I ask. She shrugs and smiles. I ask if living in the mountains is difficult. She says not particularly. Some days are difficult, but living in a city has its own hardships.